Chapter 14 Evidence Quality

Chapter leads: Patrick Ryan & Jon Duke

14.1 Attributes of Reliable Evidence

Before embarking on any journey, it can be helpful to envision what the ideal destination might look like. To support our journey from data to evidence, we highlight desired attributes that can underlie what makes evidence quality reliable.

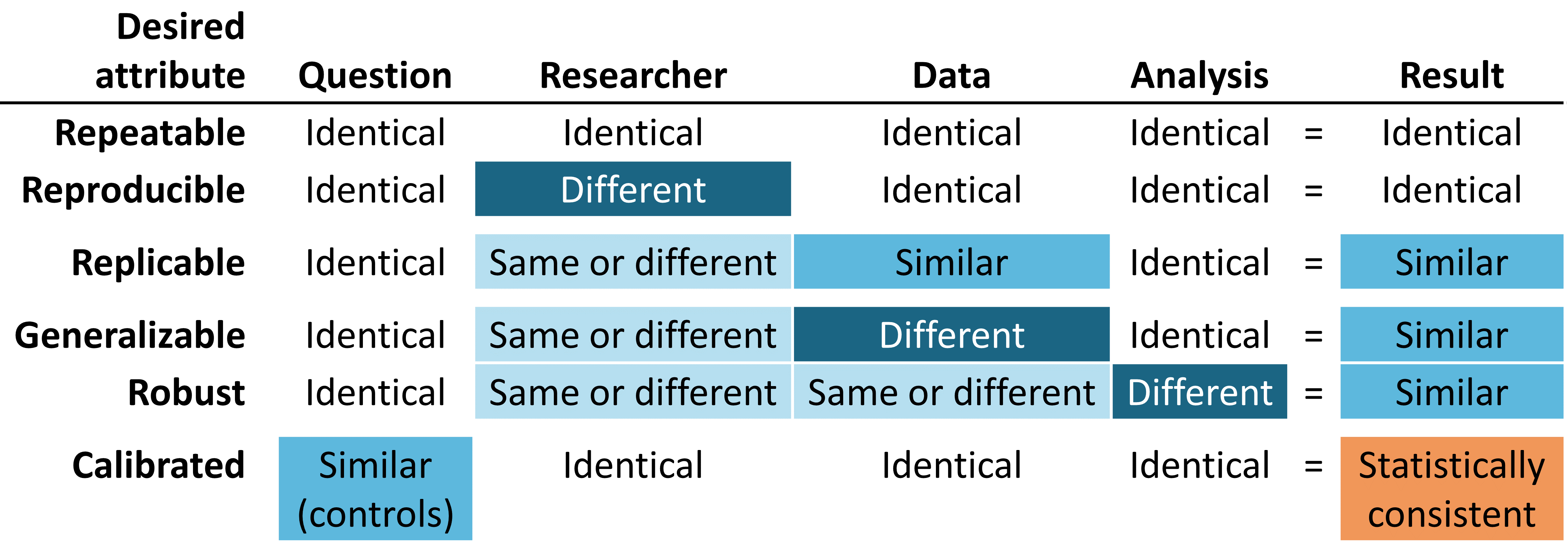

Figure 14.1: Desired attributes of reliable evidence

Reliable evidence should be repeatable, meaning that researchers should expect to produce identical results when applying the same analysis to the same data for any given question. Implicit in this minimum requirement is the notion that evidence is the result of the execution of a defined process with a specified input, and should be free of manual intervention of post-hoc decision-making along the way. More ideally, reliable evidence should be reproducible such that a different researcher should be able to perform the same task of executing a given analysis on a given database and expect to produce an identical result as the first researcher. Reproducibility requires that the process is fully-specified, generally in both human-readable and computer-executable form such that no study decisions are left to the discretion of the investigator. The most efficient solution to achieve repeatability and reproducibility is to use standardized analytics routines that have defined inputs and outputs, and apply these procedures against version-controlled databases.

We are more likely to be confident that our evidence is reliable if it can be shown to be replicable, such that the same question addressed using the identical analysis against similar data yield similar results. For example, evidence generated from an analysis against an administrative claims database from one large private insurer may be strengthened if replicated on claims data from a different insurer. In the context of population-level effect estimation, this attribute aligns well with Sir Austin Bradford Hill’s causal viewpoint on consistency, “Has it been repeatedly observed by different persons, in different places, circumstances and times?…whether chance is the explanation or whether a true hazard has been revealed may sometimes be answered only by a repetition of the circumstances and the observations.” (Hill 1965) In the context of patient-level prediction, replicability highlights the value of external validation and the ability to evaluate performance of a model that was trained on one database by observing its discriminative accuracy and calibration when applied to a different database. In circumstances where identical analyses are performed against different databases and still show consistently similar results, we have further gain confidence that our evidence is generalizable. A key value of the OHDSI research network is the diversity represented by different populations, geographies and data capture processes. Madigan et al. (2013) showed that effect estimates can be sensitive to choice of data. Recognizing that each data source carries with it inherent limitations and unique biases that limit our confidence in singular findings, there is tremendous power in observing similar patterns across heterogeneous datasets because it greatly diminishes the likelihood that source-specific biases alone can explain the findings. When network studies show consistent population-level effect estimates across multiple claims and EHR databases across US, Europe and Asia, they should be recognized as stronger evidence about the medical intervention that can have a broader scope to impact medical decision-making.

Reliable evidence should be robust, meaning that the findings should not be overly sensitive to the subjective choices that can be made within an analysis. If there are alternative statistical methods that can be considered potentially reasonable for a given study, then it can provide reassurance to see that the different methods yield similar results, or conversely can give caution if discordant results are uncovered. (Madigan, Ryan, and Schuemie 2013) For population-level effect estimation, sensitivity analyses can include high-level study design choice, such as whether to apply a comparative cohort or self-controlled case series design, or can focus on analytical considerations embedded within a design, such as whether to perform propensity score matching, stratification or weighting as a confounding adjustment strategy within the comparative cohort framework.

Last, but potentially most important, evidence should be calibrated. It is not sufficient to have an evidence generating system that produces answers to unknown questions if the performance of that system cannot be verified. A closed system should be expected to have known operating characteristics, which should be able to measured and communicated as context for interpreting any results that the system produces. Statistical artifacts should be able to be empirically demonstrated to have well-defined properties, such as a 95% confidence interval having 95% coverage probability or a cohort with a predicted probability of 10% having a observed proportion of events in 10% of the population. An observational study should always be accompanied by study diagnostics that test assumptions around the design, methods, and data. These diagnostics should be centered on evaluating the primary threats to study validity: selection bias, confounding, and measurement error. Negative controls have been shown to be a powerful tool for identifying and mitigating systematic error in observational studies. (Schuemie et al. 2016; Schuemie, Hripcsak, et al. 2018; Schuemie, Ryan, et al. 2018)

14.2 Understanding Evidence Quality

But how do we know if the results of a study are reliable enough? Can they be trusted for use in clinical settings? What about in regulatory decision-making? Can they serve as a foundation for future research? Each time a new study is published or disseminated, readers must consider these questions, regardless of whether the work was a randomized controlled trial, an observational study, or another type of analysis.

One of the concerns that is often raised around observational studies and the use of “real world data” is the topic of data quality. (Botsis et al. 2010; Hersh et al. 2013; Sherman et al. 2016) Commonly noted is that data used in observational research were not originally gathered for research purposes and thus may suffer from incomplete or inaccurate data capture as well as inherent biases. These concerns have given rise to a growing body of research around how to measure, characterize, and ideally improve data quality. (Kahn et al. 2012; Liaw et al. 2013; Weiskopf and Weng 2013) The OHDSI community is a strong advocate of such research and community members have led and participated in many studies looking at data quality in the OMOP CDM and the OHDSI network. (Huser et al. 2016; Kahn et al. 2015; Callahan et al. 2017; Yoon et al. 2016)

Given the findings of the past decade in this area, it has become apparent that data quality is not perfect and never will be. This notion is nicely reflected in this quote from Dr. Clem McDonald, a pioneer in the field of medical informatics:

Loss of fidelity begins with the movement of data from the doctor’s brain to the medical record.

Thus, as a community we must ask the question – given imperfect data, how can we achieve reliable evidence?

The answer rests in looking holistically at “evidence quality”: examining the entire journey from data to evidence, identifying each of the components that make up the evidence generation process, determining how to build confidence in the quality of each component, and transparently communicating what has been learned each step along the way. Evidence quality considers not only the quality of observational data but also the validity of the methods, software, and clinical definitions used in our observational analyses.

In the following chapters, we will explore four components of evidence quality listed in Table 14.1.

| Component of Evidence Quality | What it Measures |

|---|---|

| Data Quality | Are the data completely captured with plausible values in a manner that is conformant to agreed-upon structure and conventions? |

| Clinical Validity | To what extent does the analysis conducted match the clinical intention? |

| Software Validity | Can we trust that the process transforming and analyzing the data does what it is supposed to do? |

| Method Validity | Is the methodology appropriate for the question, given the strengths and weaknesses of the data? |

14.3 Communicating Evidence Quality

An important aspect of evidence quality is the ability to express the uncertainty that arises along the journey from data to evidence. The overarching goal of OHDSI’s work around evidence quality is to produce confidence in health care decision-makers that the evidence generated by OHDSI – while undoubtedly imperfect in many ways – has been consistently measured for its weaknesses and strengths and that this information has been communicated in a rigorous and open manner.

14.4 Summary

The evidence we generate should be repeatable, reproducible, replicable, generalizable, robust, and calibrated.

Evidence quality considers more than just data quality when answering whether evidence is reliable:

- Data Quality

- Clinical Validity

- Software Validity

- Method Validity

When communicating evidence, we should express the uncertainty arising from the various challenges to evidence quality.

References

Botsis, Taxiarchis, Gunnar Hartvigsen, Fei Chen, and Chunhua Weng. 2010. “Secondary Use of Ehr: Data Quality Issues and Informatics Opportunities.” Summit on Translational Bioinformatics 2010: 1.

Callahan, Tiffany J, Alan E Bauck, David Bertoch, Jeff Brown, Ritu Khare, Patrick B Ryan, Jenny Staab, Meredith N Zozus, and Michael G Kahn. 2017. “A Comparison of Data Quality Assessment Checks in Six Data Sharing Networks.” eGEMs 5 (1).

Hersh, William R, Mark G Weiner, Peter J Embi, Judith R Logan, Philip RO Payne, Elmer V Bernstam, Harold P Lehmann, et al. 2013. “Caveats for the Use of Operational Electronic Health Record Data in Comparative Effectiveness Research.” Medical Care 51 (8 0 3): S30.

Hill, A. B. 1965. “THE ENVIRONMENT AND DISEASE: ASSOCIATION OR CAUSATION?” Proc. R. Soc. Med. 58 (May): 295–300.

Huser, Vojtech, Frank J. DeFalco, Martijn Schuemie, Patrick B. Ryan, Ning Shang, Mark Velez, Rae Woong Park, et al. 2016. “Multisite Evaluation of a Data Quality Tool for Patient-Level Clinical Data Sets.” EGEMS (Washington, DC) 4 (1): 1239. https://doi.org/10.13063/2327-9214.1239.

Kahn, Michael G., Jeffrey S. Brown, Alein T. Chun, Bruce N. Davidson, Daniella Meeker, P. B. Ryan, Lisa M. Schilling, Nicole G. Weiskopf, Andrew E. Williams, and Meredith Nahm Zozus. 2015. “Transparent Reporting of Data Quality in Distributed Data Networks.” EGEMS (Washington, DC) 3 (1): 1052. https://doi.org/10.13063/2327-9214.1052.

Kahn, Michael G, Marsha A Raebel, Jason M Glanz, Karen Riedlinger, and John F Steiner. 2012. “A Pragmatic Framework for Single-Site and Multisite Data Quality Assessment in Electronic Health Record-Based Clinical Research.” Medical Care 50.

Liaw, Siaw-Teng, Alireza Rahimi, Pradeep Ray, Jane Taggart, Sarah Dennis, Simon de Lusignan, B Jalaludin, AET Yeo, and Amir Talaei-Khoei. 2013. “Towards an Ontology for Data Quality in Integrated Chronic Disease Management: A Realist Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Medical Informatics 82 (1): 10–24.

Madigan, D., P. B. Ryan, and M. Schuemie. 2013. “Does design matter? Systematic evaluation of the impact of analytical choices on effect estimates in observational studies.” Ther Adv Drug Saf 4 (2): 53–62.

Madigan, D., P. B. Ryan, M. Schuemie, P. E. Stang, J. M. Overhage, A. G. Hartzema, M. A. Suchard, W. DuMouchel, and J. A. Berlin. 2013. “Evaluating the impact of database heterogeneity on observational study results.” Am. J. Epidemiol. 178 (4): 645–51.

Schuemie, M. J., G. Hripcsak, P. B. Ryan, D. Madigan, and M. A. Suchard. 2016. “Robust empirical calibration of p-values using observational data.” Stat Med 35 (22): 3883–8.

Schuemie, M. 2018. “Empirical confidence interval calibration for population-level effect estimation studies in observational healthcare data.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115 (11): 2571–7.

Schuemie, M. J., P. B. Ryan, G. Hripcsak, D. Madigan, and M. A. Suchard. 2018. “Improving reproducibility by using high-throughput observational studies with empirical calibration.” Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 376 (2128).

Sherman, Rachel E, Steven A Anderson, Gerald J Dal Pan, Gerry W Gray, Thomas Gross, Nina L Hunter, Lisa LaVange, et al. 2016. “Real-World Evidence—What Is It and What Can It Tell Us.” N Engl J Med 375 (23): 2293–7.

Weiskopf, Nicole Gray, and Chunhua Weng. 2013. “Methods and Dimensions of Electronic Health Record Data Quality Assessment: Enabling Reuse for Clinical Research.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association: JAMIA 20 (1): 144–51. https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000681.

Yoon, D., E. K. Ahn, M. Y. Park, S. Y. Cho, P. Ryan, M. J. Schuemie, D. Shin, H. Park, and R. W. Park. 2016. “Conversion and Data Quality Assessment of Electronic Health Record Data at a Korean Tertiary Teaching Hospital to a Common Data Model for Distributed Network Research.” Healthc Inform Res 22 (1): 54–58.